While Rachel Bellamy watched her uncle graduate from the U.S. Army Military Academy at West Point in 1979, she noticed something peculiar about the graduating class. The five-year-old daughter of an enlisted U.S. Army soldier was curious why she didn’t see any women among the cadets graduating. Her uncle was among the 900 graduating cadets of the last all-male class at West Point, ending a 117-year tradition of exclusion. The following year, 62 trailblazing women would walk across the parade field and into history, paving the way for Bellamy to achieve a life-long goal she set at her uncle’s graduation.

While Rachel Bellamy watched her uncle graduate from the U.S. Army Military Academy at West Point in 1979, she noticed something peculiar about the graduating class. The five-year-old daughter of an enlisted U.S. Army soldier was curious why she didn’t see any women among the cadets graduating. Her uncle was among the 900 graduating cadets of the last all-male class at West Point, ending a 117-year tradition of exclusion. The following year, 62 trailblazing women would walk across the parade field and into history, paving the way for Bellamy to achieve a life-long goal she set at her uncle’s graduation.

“I was watching everything and observed that there were no skirts walking across the parade field. I turned to my mother and said, ‘Mom! There’s no skirts’,” Bellamy said. “Then I told them I was going to go to West Point, and my grandmother kind of laughed. I don’t think she meant it like I received it, but from that point on if anybody asked what I was going to do, my answer was always, ‘I’m going to West Point.’”

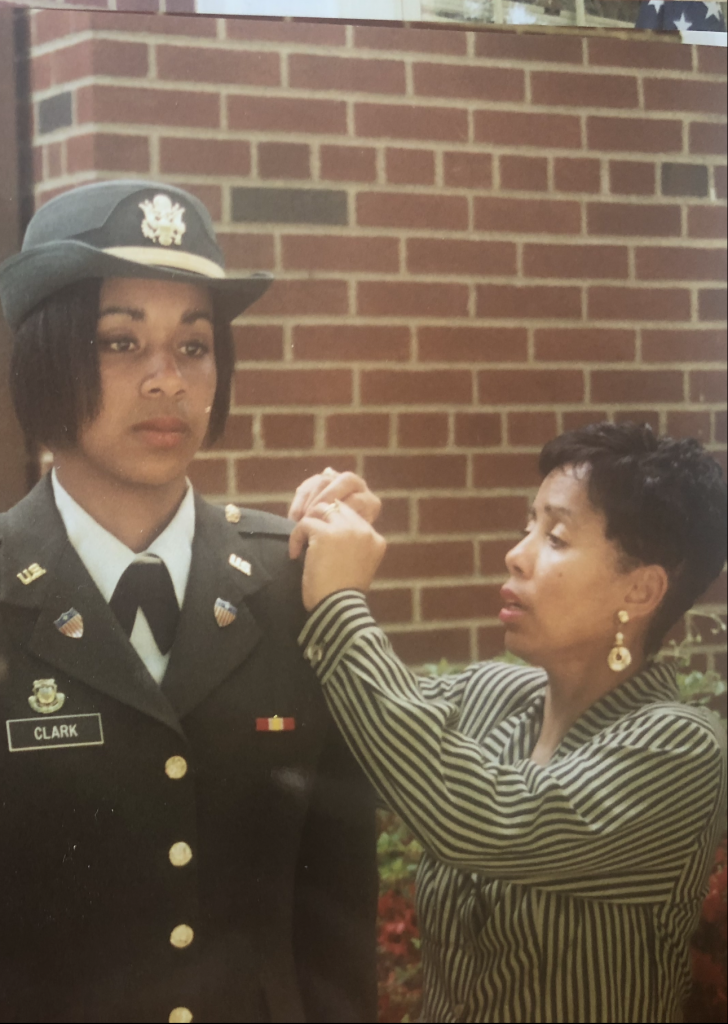

For young girls at the time it was nearly an impossible goal to achieve. Just getting into the academy as a woman was difficult back then, graduating was an entirely different challenge. However, in 1997, the self-proclaimed fourth-generation army brat, walked across West Point’s parade field, in a skirt, and earned herself a commission in the U.S. Army.

That determination was instilled early in Rachel’s life. As many military children experience, Bellamy, whose maiden name at the time was Rachel Clark, grew up moving from base to base on an almost cyclical basis. Each move came with the need to settle into a new community, a new home, and make new friends every few years.

“When you’re only going to be somewhere for 18 months, you have to make friends fast. We have to get over all the drama,” said Bellamy. “I think that it served me well later in life. I tend to just jump in, get through the pleasantries, and just go for it.”

Rachel’s determination and resiliency were tested on many occasions before reporting for her first day at West Point. Interruptions to her education with every change of duty station was routine for her and taken in stride. At the age of 14, Bellamy and her parents would endure a catastrophic loss when her father, then stationed in Germany, suddenly passed away from medical complications.

Rachel’s determination and resiliency were tested on many occasions before reporting for her first day at West Point. Interruptions to her education with every change of duty station was routine for her and taken in stride. At the age of 14, Bellamy and her parents would endure a catastrophic loss when her father, then stationed in Germany, suddenly passed away from medical complications.

“From that point on I was the child of a single mom, and that kind of became our story,” Bellamy said. “Back then that was a big deal. If your parents were divorced, or your mom was a widow, people thought you came from a dysfunctional home,” Bellamy said.

Being a woman at West Point wouldn’t be her only challenge during her four years at the famed military academy. Many historic military institutions were slow to culturally adapt after desegregation. Executive Order 9981, signed by President Harry S. Truman in 1948, effectively ended segregation in the military, but the change was slow to transition from paper to practice among the ranks.

“I remember when I told my uncle that I was serious about going to West Point, he said, ‘Well, I need to let you know some things.’ He told me there were going to be some uncomfortable times, and not just because it’s hard academically, but also because I was Black.” Bellamy said.

Bellamy wasn’t naïve to the situation; in fact, she charged headfirst into the fray. She consistently turned others’ perceptions of her, especially their presumptions about her potential due to her skin color, into an advantage.

She could have easily opted for an easier college experience. Her academic performance in high school had garnered multiple scholarships, including a full ride to Spelman College, a historically Black liberal arts college for women in Atlanta.

“I could have gone to Spelman, where I would have been among 1,000 other strong Black women, or I could go to West Point and have a bigger impact,” Bellamy said, but the decision was not without sacrifice.

For the first two years, Bellamy recalls spending a lot of mental and emotional energy trying to figure out which prejudgment she had to combat whenever she entered a room.

For the first two years, Bellamy recalls spending a lot of mental and emotional energy trying to figure out which prejudgment she had to combat whenever she entered a room.

“If they saw me as female, then it was a prejudice that I wasn’t strong or not strategic. If they saw me as black, then it was a prejudice that I wasn’t smart, or was only at the academy because she was an athlete,” said Bellamy.

Whenever faced with such misjudgments of her, she would try to outperform to combat the prejudgment. She remembers those days being exhausting, but she also remembers her mentor, Lieutenant Colonel Price, who gave her life-changing advice during her sophomore year.

“She told me, ‘If you already have their attention, make not just an impression, make an impact,’ and that’s what I aimed to do,” Bellamy said.

While she recalls plenty of microaggressions during her time at West Point, Bellamy says there is one particular instance that stood out to her. During one of her classes on armor tactics, her instructor, a Major, openly made a disparaging comment that was far enough over the line that it garnered attention from the entire class.

“This instructor told me I probably wouldn’t understand the material. A number of my classmates heard it, and said it was messed up,” Bellamy said. “When I got the highest score on the test, the Major actually reprimanded the class. He asked the guys, ‘How dare you let a female beat you?’”

“This instructor told me I probably wouldn’t understand the material. A number of my classmates heard it, and said it was messed up,” Bellamy said. “When I got the highest score on the test, the Major actually reprimanded the class. He asked the guys, ‘How dare you let a female beat you?’”

Bellamy went on to serve for five years in the Army, ultimately earning the rank of Captain. Her years in the military were mostly spent with the Adjutant General’s Corps, a specific branch within the Army that focuses on human resources and talent management, as well as data collection and analysis to communicate human resources information to senior leadership. She and her husband, both fourth generation veterans, would meet while serving in the Army together, and after their commitments were up, they both left the military to start a family.

Rachel’s background and experience were once again put to the test when she later joined the federal government as a Program Manager for Leadership and Knowledge Management with the Office of Personnel Management. At the time, the U.S. Government was aware that a void in leadership was approaching with a large wave of upcoming retirements. Bellamy’s task was to make sure the federal agencies had a plan.

“I had to go and validate that every federal agency had a plan to replace leaders as people left, and I loved that job,” said Bellamy. “One of the things I would talk about, and one of the beautiful things I appreciate about the military, is how it gave me a safe place to make mistakes as a leader. In the government, that’s not the case. You don’t get to lead people until you’re at a much higher pay grade and by that time, it’s a little late to be trying things out.”

She and her husband, Lonnie Bellamy now own a business together in Northern Virginia. As the Executive Vice President of TIME Systems, a full-service management, consulting, and information technology company, Bellamy has the ability to lean on her experience to help develop the next generation of leaders.

Bellamy would later graduate from the Veteran Women Igniting the Spirit of Entrepreneurship program, which teaches military-connected women the fundamentals of entrepreneurship while addressing the unique challenges women face in owning a business. Now, she gives back to the military-affiliated entrepreneurship community by sharing her knowledge at IVMF events like Veteran EDGE.

TIME Systems continues to grow year over year, in part due to the resources and relationships gained from organizations like IVMF and its affiliated events. TIME Systems has consistently ranked on the Inc. 5000 list, both national and regional, the Vets 100 list, and others. These lists rank the most dynamic and innovative companies. TIME Systems has grown to 100 employees, and over $12 million in annual revenue. TIME continues to expand its capabilities in several focus areas, such as Cyber Security Training, Software Development, and IT Helpdesk Support.

After military service, Rachel and her husband had four children together. Their oldest son, Elijah, is currently a junior at West Point, continuing the legacy of leadership started by her uncle David Clark, in 1979. Before her son left to tackle the grueling four years, Rachel says she had to have a conversation with him about the challenges with prejudice and racism at the West Point and in the military, like the conversation her uncle had with her.

“It was tough to have that conversation with him, but I needed for him to know how he would respond when it did happen,” Bellamy said. “We serve and we fight for the hope that one day America will be what she has the potential to be.”